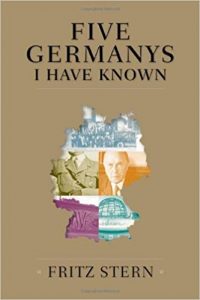

Recent events have inspired me to re-read Fritz Stern‘s book Five Germanys I have known (grammar nerds will note that it is “Germanys,” not “Germanies,” because the usual plural spelling rules don’t apply to proper names), specifically the middle section about nurturing, preserving, and defending liberal democracy.

Reading this book ten years ago, I skimmed that part thinking, “Yeah, mm-hmm, whatever.” But it all seems terribly relevant now. Take his comments on the student revolts of ’68, when he was teaching at Columbia University:

I was angry at the jubilant desecration of the university, and afraid that we were betraying our patrimony. […] I was afraid of the radical youths who were intoxicated by their own rhetoric, enthralled by the initial successes of violence, and convinced of their historic role as iconoclasts. […] Their disruptions were not cost-free: I feared a massive backlash, a reaction by conservative yahoos who would feel justified in their paranoid hatred of liberal (and expensive) institutions.

How relevant.

Then there was a rising desire on the right for repressive law and order, along with a “professed faith in the virtues of hard work and economic individualism, and contempt for the welfare state that ‘coddled’ the weak…a new version of Social Darwinism, bloody-minded if economically effective.” And there were advocates of la politique du pire — “that delusionary policy that holds that the worse things go, the better for radicals. I have often fought with these self-righteous ‘wreckers,’ who seldom realize how bad and irredeemable things can get.”

Ditto.

Having fled Nazi Germany for an America that was — on the whole and despite its economic woes — confident, well-meaning and optimistic, with a president who insisted the only thing to fear was Fear itself, Stern was wary of radicals on the left and right. Like G. K. Chesterton, he understood that it was worthwhile, and an adventure, to keep your horse running straight when it is tempted to veer onto the paths that lead to insane extremes.

He gave an interview to Greenpeace magazine in January 2016, a few months before his death at age 90. The interview seems to be available only in German, so I’ve taken the liberty of translating an excerpt here:

Historian Fritz Stern: “We are facing an era of fear.”

GP: Is Europe moving too far to the right?

FS: I fear it is. I believe we are facing an era of fear, widespread fear — the fear that can be exploited by the right. And you can already see in the example of Poland how fragile freedom is. It is shocking how quickly an authoritarian system is being built up in Poland. […] And as an American citizen I am also deeply concerned.

GP: About what comes after Barack Obama?

FS: Precisely. On the whole I’m an admirer of Obama and it was a great achievement on the part of this country to have elected him twice. But the current situation is so serious, so destructive, so dysfunctional, that it can only make you worry.

GP: You mean Donald Trump?

FS: Trump is the best example of the dumbing-down of the country and the appalling role of money. An absolutely amoral guy who flaunts his money and ignorance. I arrived in this country when Franklin Roosevelt was president. That someone like Trump, who is a nobody apart from money and monstrous ambition and ugliness – that he would not only put himself forward but would even be accepted by many people as a candidate, is simply beyond comprehension.

GP: What has changed in American society?

FS: I’ve already spoken of dumbing-down. That is due in large part to the media and to the fact that there are fewer and fewer objective journalists. Most people can choose the ones who preach what they want to hear. […] A certain kind of new religiosity, which has very little to do with true religiosity, is also on the rise. I believe we are facing a new illiberal age. And for someone who dedicated his life to a certain liberalism, those are sad tidings. It’s a decline.

RIP Prof. Stern. If there’s anything I can do to keep that horse on the trail, I’ll do it.