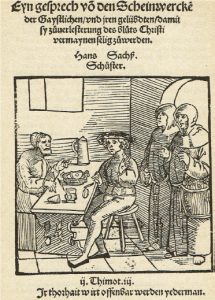

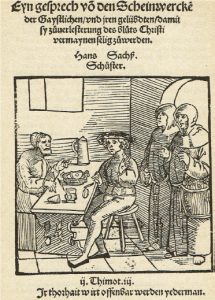

In honor of the 500th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses, here is my heavily redacted version of a Reformation-era dialogue by Hans Sachs, namely

A dialogue on the hypocrisy of the religious and their vows, through which, despising the blood of Christ, they presume to become holy.

in which Hans the cobbler and Peter the baker amuse themselves by trolling an unsuspecting Franciscan friar who just wants some candles. These dialogue pamphlets dramatizing theological disputes were very popular in the 16th century. Here the Franciscan friar attempts to defend traditional Catholic religious orders against Protestant objections. Like most Reformation dialogues, this one contains lengthy passages where the speakers just sling competing Bible verses at each other. I’ve cut most of that out and kept the fun stuff. Although this is a loose translation, it’s still fairly accurate. Enjoy!

Monk[1]: Peace be with you, dear brethren! Of your charity please give me some alms for the poor barefoot Franciscans, we need candles for singing and reading.

Peter: I don’t give to strong beggars like you and begging is forbidden. In Deut. XV God says, “There shall be no beggars among you.” I give candles to my poor neighbors who use them for WORKING. Get a job!

Monk: Ah, you must be Lutheran.

Peter: Nope, Evangelical.[2]

Monk: Then yeesh, do what the Gospel tells you and give to anyone who asks of you. Matthew V, Luke VI, and so on…

Hans: He just roasted you with Bible verses, Peter.

Peter: OK fine, I got roasted. Here brother Heinrich, behold this penny which I will give you for the Lord’s sake and which you can exchange for whatever candle suits your fancy.

Monk: Oh, God protect me, I’m not allowed to take money! My order forbids it.

Hans: Who set that order up?

Monk: Our holy father Francis.

Hans: Oh, so Francis is your father? Well GUESS WHAT – Christ says in Matthew XXIII to call no man “father,” for you have but one father who is in heaven!

Monk: Arrgh, we know that. But he taught us the way a good father teaches his children.

Hans: Then I guess he’s your master and you can’t call any man “master” either, according to Christ in that same chapter, and Christ says again in John’s Gospel that he is the way the truth and the life, which isn’t really relevant but I feel like I need more Bible verses to back up my argument.

Monk: But Francis didn’t just make things up himself, he took them from the Holy Gospel.

Hans: Where in the Gospel does it say you can’t touch money? I can give you the opposite example. Remember when Christ told Peter to catch a fish and open it up and there was a coin inside? That was amazing.

Monk: But he also said not to build up treasure on earth, and you cannot serve God and mammon, and Luke XII, and then there’s the camel and the eye of the needle, and sell all you have and give it to the poor…there you have it.

Hans: You talk the talk, Mr. No-Shoes, but do you walk the walk?

Monk: Um, yes? We don’t take any money, which means we don’t have any. Not even a little.

Hans: But outside your cloister walls you have plenty of friends taking and spending money for you…princes who build your snazzy monasteries and pay thousands of ducats for you to buy a cardinal’s hat. Don’t think we haven’t noticed. If that’s not called “building up treasure on earth”, I don’t know what is.

Peter: It’s called playing your greed under your little hat.

Monk: OK what the – look, fine, we have people who look after the money for us. But we don’t pay any attention to money. We focus on our religious duties.

[extended conversation about money, including the accusation that money donated to religious orders is ultimately being stolen from The Working Man]

Hans: …and you’re no use to God or man.

Monk: It might make sense to say that if we didn’t spend LITERALLY ALL OUR TIME SERVING GOD!!!

Hans: You’re good at going to church, not so great at doing actual works of mercy.

Monk: Come to our monastery tomorrow at noon! You’ll see a whole pile of poor people getting fed.

Peter: Yeah, you give them the food you don’t want, like soup and peas, then you sit in your own refectory eating delicious fish soup and vegetables with no sense of shame!

[boring section cut]

Monk: Well God bless you, young men, but I have to move on now to someone who might actually give us something.

Hans: Wait, wait Brother Heinrich! One more thing.

Monk: WHAT

Hans: Do you keep your vow of chastity?

Monk: Yes, why not? If we didn’t know how to keep that vow, we wouldn’t make it.

Peter: The farmer’s daughters really get a taste of your chastity when you’re out collecting cheese.[3]

Monk: Show me where it says that in our rule!

Peter: I don’t mean just you guys…it’s all the mendicants who are out there collecting cheese.

Monk: Don’t judge the whole crop by a few weeds.

Hans: My concern is that if you don’t do things the natural way, you’ll end up getting into the freaky stuff….

Monk: That’s why we discipline our flesh. Our whole rule is designed to curb the desires of the flesh. Not just by fasting, but other kinds of discipline too.

Peter: Tell us about it…

Monk: Happy to! We don’t wear any linen underwear, but we do wear rope belts, we go barefoot in open shoes[4], we don’t wear any hair on our heads, we go our entire lives without taking a bath – seriously, until we die – we don’t sleep on feathers, we never take our clothes off, we eat meat at not quite half our meals, we don’t eat off of tin[5], we have to be quiet A LOT, we have to stand and kneel in the choir for an hour or five every day, and pray in the middle of the night.

Peter: Oh yeah? Well the guys and I work really hard every day for crappy food and then we get to bed late, and in the morning the kids are already up yapping by matins…I think my rule is harder than yours.

[interminable argument cut]

Peter: Look Brother Heinrich, I have two candles for you. But don’t use them to read Scotus or Bonaventure. Read the Bible and eventually God will enlighten you. And don’t be offended by the way we jumped down your throat and harangued you for an hour when you could have been out collecting more candles.

Monk: It’s OK, dear brethren. God be with you.

Peter: AMEN.

Epilogue: Peter and Hans were saved by faith alone and went to Heaven even though they were jerks. Their many descendants refuse to go to bed when somebody is wrong on the Internet.

Brother Heinrich asked the prior if he could be put on cheese collecting duty next time. He is still in Purgatory.

[1] Actually a friar.

[2] The idea here is probably not that Peter disapproves of Luther, but that “Evangelical” is a better term with more legitimacy, since it basically means “a follower of the Gospel” (as opposed to a follower of one specific guy).

[3] “keß” in my edition, “kes” in another one. I think that must be cheese… Collecting cheese was apparently such an occasion of sin that Sachs wrote a jaunty little couplet about it: “Mein keuschheit ich frei halten tet / wenn ich nicht kās zuo samlen het” (“I’d keep my chastity with ease / if I didn’t go out collecting cheese”). For more on cheese and chastity, see here.

[4] So…not actually barefoot?

[5] “essen aus kainem zin”?