We don’t need to talk about German all the time here. Let’s consider a tongue known for its siren-like hold over language nerds: Welsh.

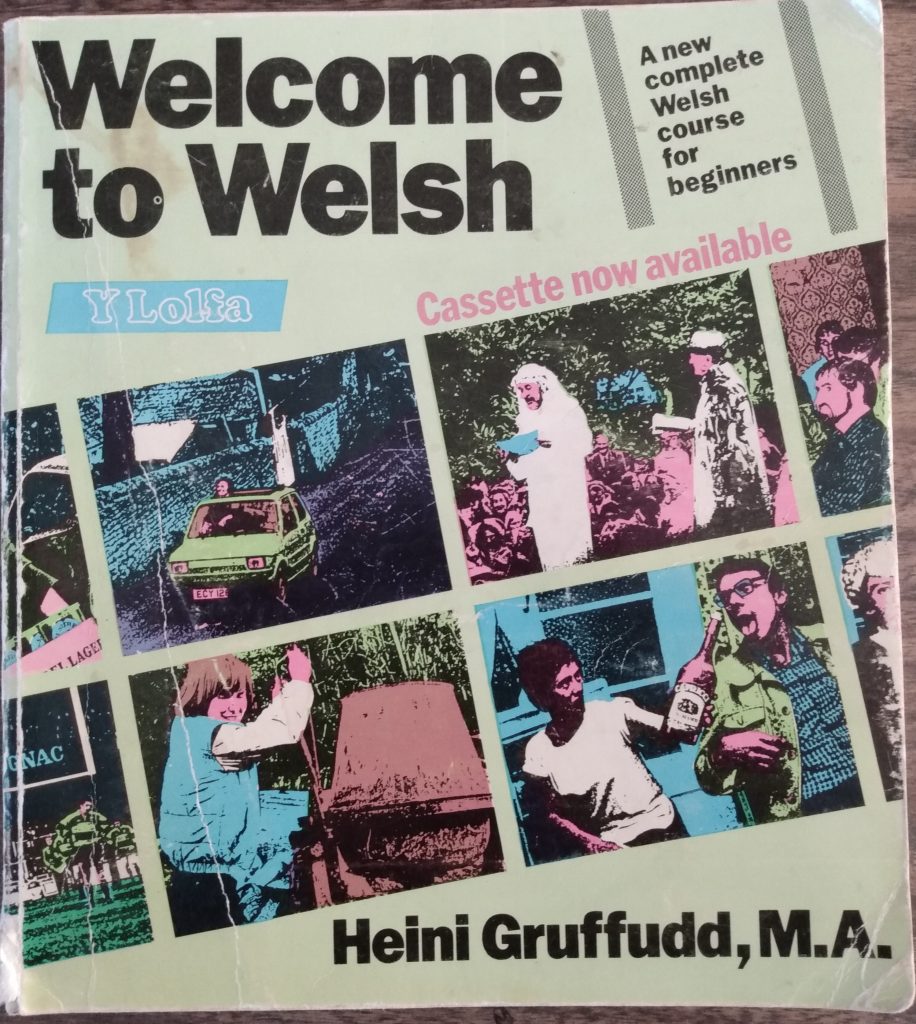

I received Welcome to Welsh from a family friend who was majoring in linguistics when I was in 8th grade in 1990. He had it, and knew I would want it, because if you have the language-learning bug, the moment you see a sentence like “Oeddech chi wedi meddwl am fynd i Landudno yn yr haf?” you know you will never be at peace until you learn to talk like that.

I’m not sure how Welsh feels to young people nowadays, but back then it enjoyed a curious status in the quieter corners of American youth culture. Not only because it was the Holy Grail of language nerds, but because it conjured the Welsh imaginary which nourished and sustained the fantasy genre. For American children who read The Chronicles of Prydain or watched The Black Cauldron, names like Gwydion and Fflewddur Fflam sounded intrinsically magical; by the time those kids got to high school, bookstores were flooded with paperback knockoffs about guys named Rhys fighting dragons on misty green islands with magic swords so they could marry Princess Gwenhwyfar and go live in the land of Ionawr or whatever.

I swear I used to see perfectly normal people reading those books, not just boys who played D&D instead of sports. Most of them probably didn’t know they were inspired by Wales – in my experience, many Americans were unaware that Wales existed and many more didn’t realize it had its own astonishing language. But anyone who developed an obsession with foreign languages or fantasy – or, God forbid, both – was sure to be pulled into the Welsh orbit. Information was scarce in those days, however. The encyclopedia could show you a map and a picture of coal miners and provide you with a few non-magical facts. You might see A Child’s Christmas in Wales on PBS. And that was about it, unless you really made an effort or had a nice friend who could send you obscure language books in the mail.

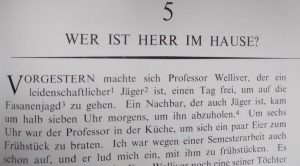

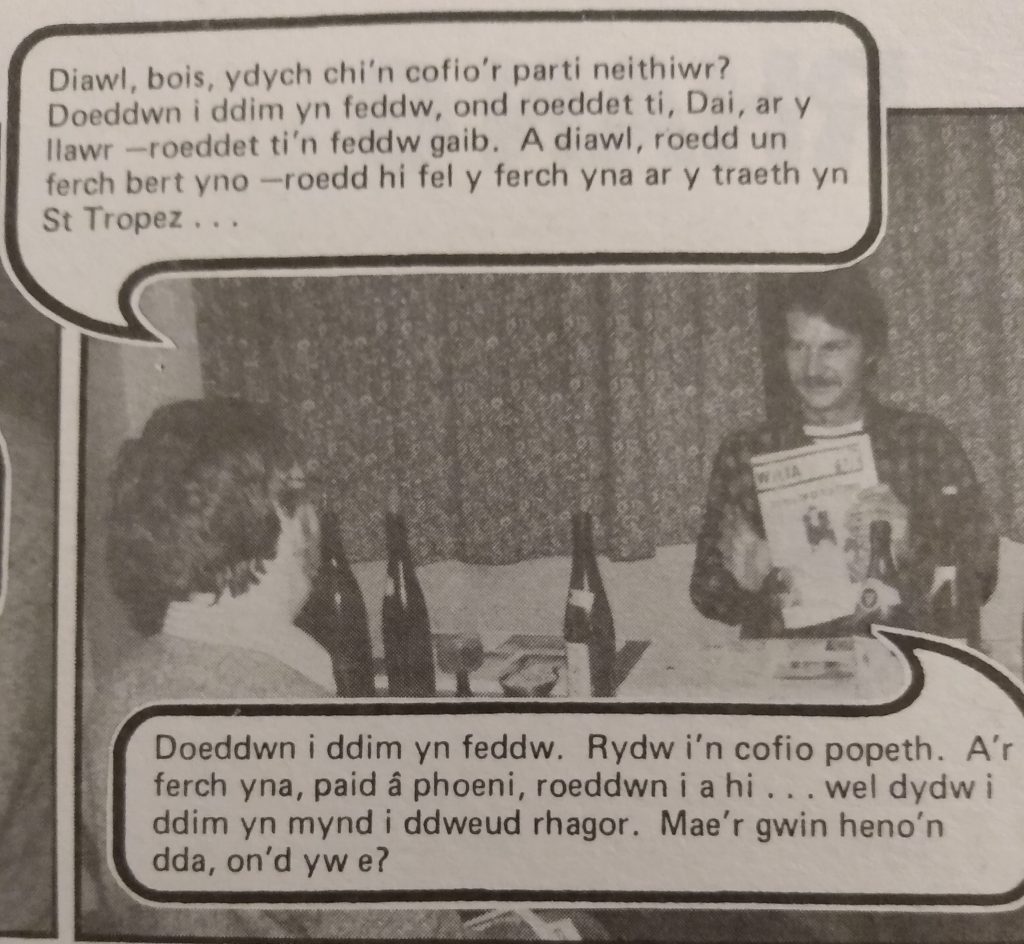

The Wales I discovered in Welcome to Welsh was not the Wales of my imagination. Published in 1984, it featured picture stories about people who were either living in the seventies or continuing to rock seventies styles, and who enjoyed watching TV, drinking to excess, and having casual affairs with door-to-door salesmen. Their material circumstances seemed rather shabby compared to the American suburb I grew up in, yet they outclassed me by going on holidays in St. Tropez.

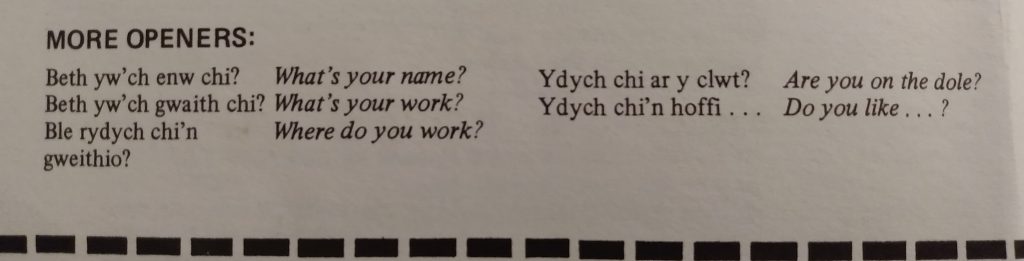

There was definitely no magic, unless wandering around the Societies Tent at the Eisteddfod counts as a magical experience. Coal (glo) is in the glossary so it’s probably mentioned somewhere, but overall there was a distinct lack of coal mining. That may be why one of the conversation openers is “Are you on the dole?” (Here the book actually taught me a new English word – I had to ask various adults before finding one who was able to inform me that it meant “Are you on welfare?”)

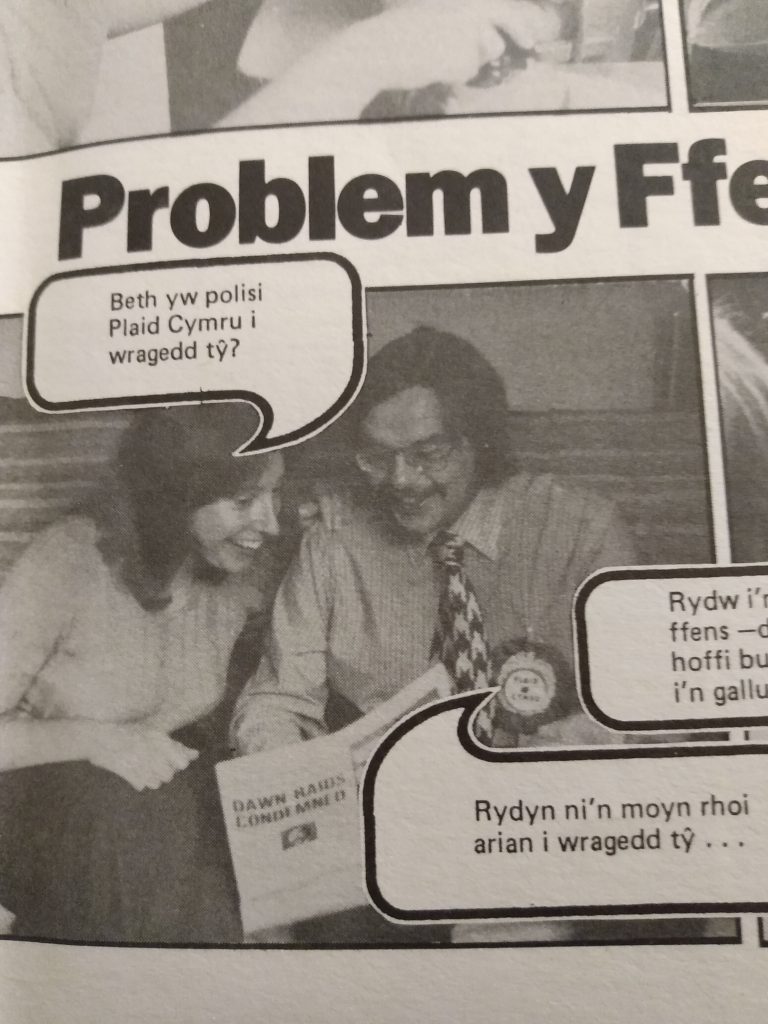

But the local Plaid Cymru candidate is on your side:

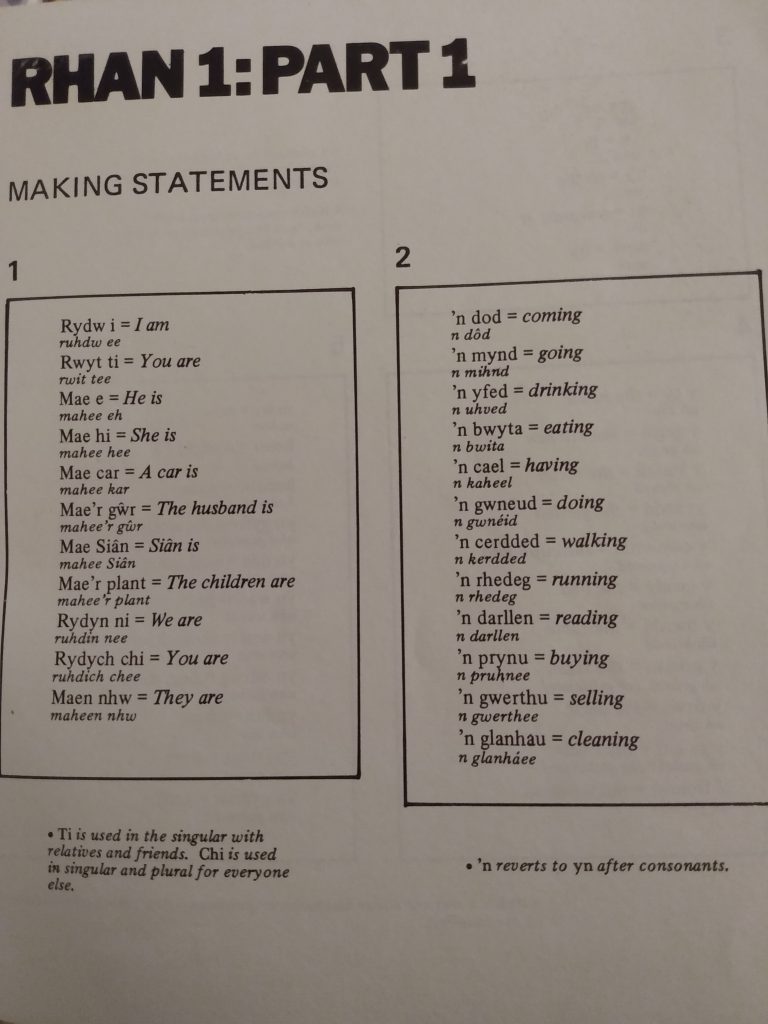

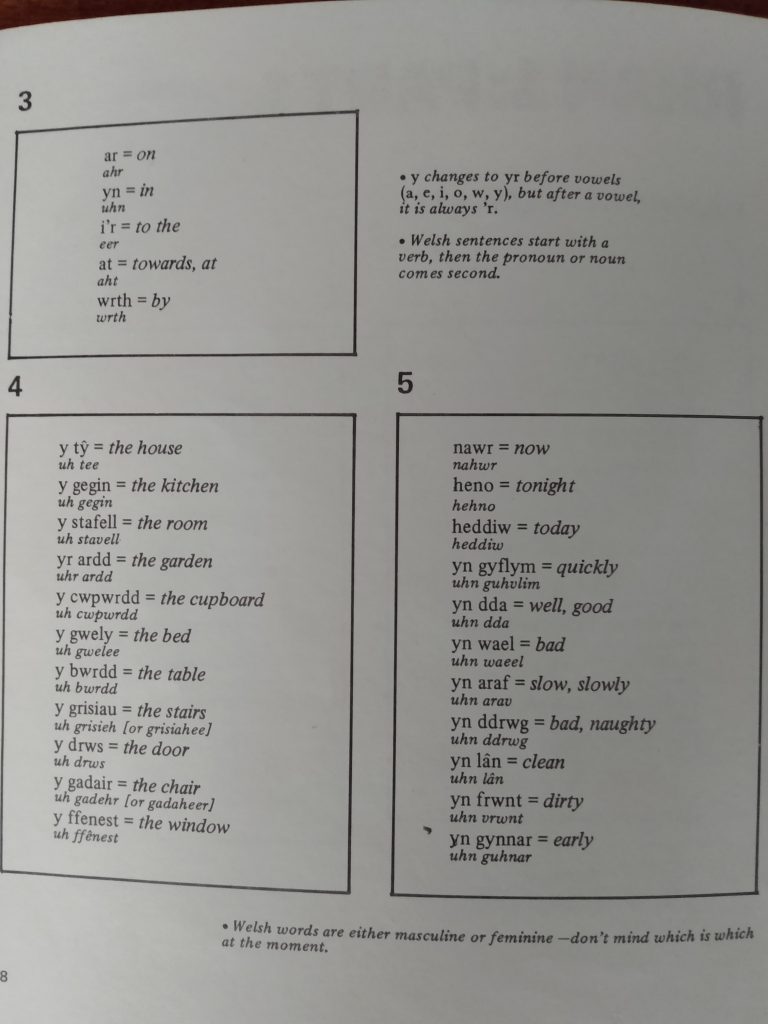

Quirky picture stories aside, Welcome to Welsh did turn out to be a highly informative and well-organized course in the Welsh language. I loved the layout and always found the lessons easy to absorb. These sentence-building boxes on the first two pages instantly enriched my life:

I learned a lot from this book. Not just about the seamy side of small-town life in Wales, but about grammar and vocabulary. I didn’t put in enough effort to become fluent, but I did once give Bryn Terfel a shock when he was signing autographs at Ravinia, so all the time I spent reading this book instead of doing schoolwork was totally worth it.

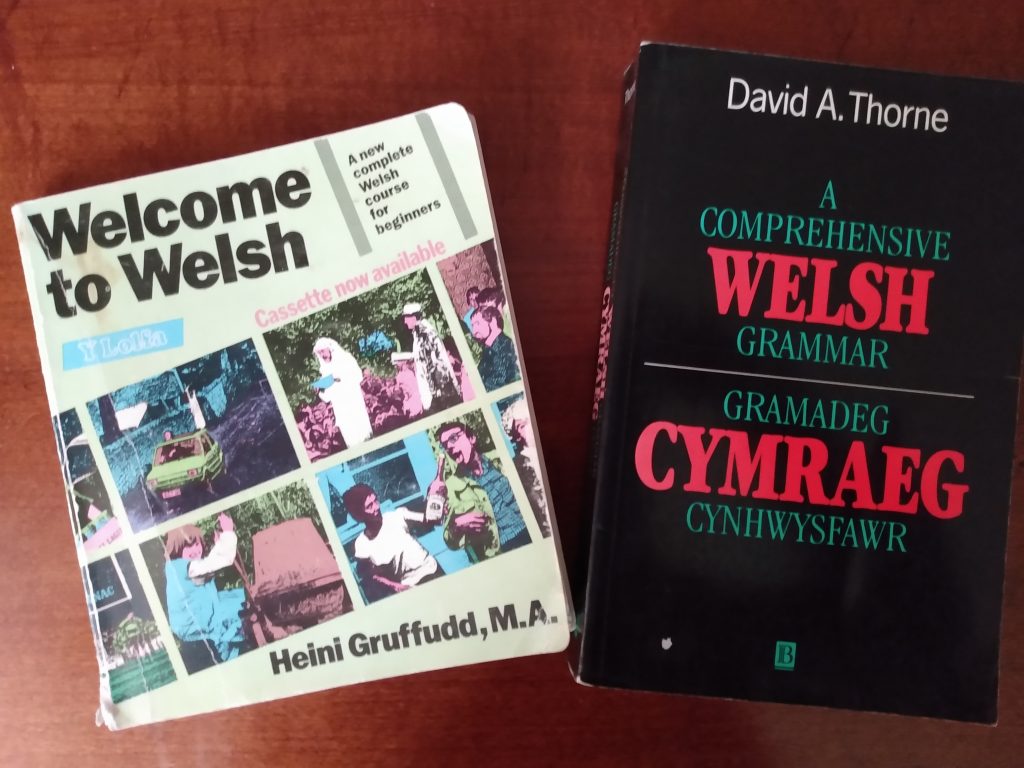

Eventually I married a fellow nerd – an alliance that gained me a Welsh book.

His is more formal and probably has better morality, but Welcome to Welsh will always be my favorite.