Translating Wolfram’s Parzival has got to be a total nightmare, though it’s probably also fun.

His style is, by his own admission, comparable to a startled hare darting this way and that. This applies to individual sentences but also to the entire narrative. Some questions you may ask yourself when reading Parzival include: Did we already meet Plihopliheri in a previous chapter or was that Plippalinot? Is everyone in this book related? How much cousin marriage is going on here? Where did those guys come from and why are they attacking that castle? Why are we talking about the neutral angels again? How many times will I have to read this sentence before I understand it? And many more.

There are three published prose translations of Parzival: a joint effort from 1961 by Helen Mustard and Charles Passage (who aren’t characters from Toast of London but probably should be), a 1980 Penguin Classics edition by A.T. Hatto, and a fairly recent effort by Cyril Edwards for Oxford World’s Classics (2004). No one in our time has been insane enough publish a rhyming-couplets version. [Update: in fact, there is a new verse translation. See here.] Jessie Weston did it in 1894, but translation standards were looser then.

I have a soft spot for Cyril Edwards’ translation because when he was working on it, he came to St. Andrews to speak to the German medievalists. He gave us a very informative presentation about his own choices and how they compared to previous editions. I particularly remember how proud he was to have found the most accurate possible translation for “ramschoup” in Book IX. Apparently after laborious research he determined it was “purple moorgrass.” Our professors thought this would sound oddly specific in context – other translators were content to call it “straw” and it’s hard to imagine one character telling another, “I don’t have furniture but you can sit on that pile of purple moorgrass over there…” – but he couldn’t bear for his research to have been in vain and insisted on keeping purple moorgrass because that’s what ramschoup is! And indeed, there it is on p. 204 of the book: “Then they went back to lie on their purple moorgrass, by their coals.”

Having recently skimmed all three translations, I suspect Mustard & Passage is the most readable. However, research into medieval literature and culture is always uncovering new things and solving little mysteries, so the fact that it came out in 1961 probably means it has more errors than the other two. These are unlikely to matter if you’re reading it for fun but if you’re a grad student, watch out.

Hatto’s has the most prosaic feel – he tends to collapse sentences or shift their parts around to avoid some of Wolfram’s twists and turns.

Both Hatto and Mustard/Passage tried to calm the startled hare of Wolfram’s style to make the reading experience less confusing. Edwards, on the other hand, says in his introduction that “this translation, in the interest of trying to convey something of Wolfram’s stylistic originality, will give the reader a rougher ride than its predecessors.”

Here are some excerpts to give you a sense of the different translations. First, from the prologue:

Mustard and Passage: I mean to tell you once again a story that speaks of great faithfulness, of the ways of womanly women and of a man’s manhood so forthright that never against hardness was it broken. Never did his heart betray him, he all steel, when he came to combat, for there his victorious hand took many a prize of praise. A brave man slowly wise – thus I hail my hero – sweetness to women’s eyes and yet to women’s hearts a sorrow, from wrongdoing a man in flight! The one whom I have thus chosen is, story-wise, as yet unborn, he of whom this adventure tells and to whom many marvels there befall.

Hatto: I will renew a tale that tells of great fidelity, of inborn womanhood and manly virtue so straight as never was bent in any test of hardness. Steel that he was, his courage never failed him, his conquering hand seized many a glorious prize when he came to battle. Dauntless man, though laggard in discretion! – Thus I salute the hero. – Sweet balm to woman’s eyes, yet woman’s heart’s disease! Shunner of all wrongdoing! As yet he is unborn to this story whom I have chosen for the part, the man of whom this tale is told and all the marvels in it.

Edwards: A story I will now renew for you, which tells of great loyalty, womanly woman’s ways, and man’s manliness so steadfast that it never bent before hardship. His heart never betrayed him there – steel he was, whenever he entered battle. His hand seized victoriously full many a praiseworthy prize. Bold was he, laggardly wise – it is the hero I so greet, woman’s eyes’ sweetness alongside woman’s heart’s desire, a true refuge from misdeed. He whom I have chosen for this purpose is, storywise, yet unborn – he of whom this adventure tells, in which many marvels will befall him.

There’s plenty to comment on here but I’ll just point out one thing: both M/P and Edwards have “storywise” where Hatto has opted for the more ordinary “to this story.” Wolfram’s word is “maereshalp” which is almost certainly his own neologism. “Storywise” is a solid translation and makes your ears perk up in the same way as the original.

Here’s what it sounds like when Lady Adventure knocks on the narrator’s heart:

Mustard and Passage:

“Open up!” – To whom? Who are you? – “I want to come into your heart to you.” – Then it is a small space you wish. – “What does that matter? Though I scarcely find room, you will have no need to complain of crowding. I will tell you now of wondrous things.” – Oh, is it you, Lady Adventure?

Hatto:

“Open!” – “To whom? Who is there?” – “I wish to enter your heart.” – “Then you want too narrow a space.” – “How is that? Can’t I just squeeze in? I promise not to jostle you. I want to tell you marvels.” – “Can it be you, Lady Adventure?”

Edwards:

“Open up!” – To whom? Who are you? – “I want to go into your heart.” – That’s a narrow space you want to enter! – “What of it, even if I barely survive! You’ll seldom have cause to complain of my jostling! I want to tell you of wonders now!” – Oh, it’s you, is it, Lady Adventure?

Big differences here in how Lady Adventure’s long response is translated. Edwards’ version might be closest to the original (“waz denne, belibe ich kume?* min dringen soltu selten clagen: ich wil dir nu von wunder sagen“) but Hatto’s sounds the most like something you might actually want to read aloud.

Which reminds me – the ideal way to experience this story is to sit with some friends and hear it recited. After all, according to Wolfram, it isn’t even a book and reading is for losers.

But however you experience it, a long engagement with this story will feel like an exhaustive tour of a Gothic cathedral that leaves you spent but filled with admiration.

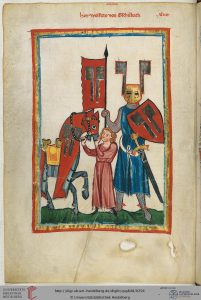

Photo credits: baby hares by Jang Woo Lee, purple moorgrass by Elke Freese, Wolfram von Eschenbach in the Codex Manesse at: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848/0294

You can access a verse translation by A. S. Kline for free here!

*(And btw I’ll admit to not being sure what “belibe ich kume” means – anyone want to enlighten me there?)

I’ve considered reading this, especially after seeing the Wagner opera a few years ago. But I had no idea what translation to read, so this post is especially helpful.

Belibe ich kume: Bleibe ich kaum (if I scarcely remain)? Admittedly, I worked that out back from the English translation.

Oh, well done! Thanks.

I’m now working through the Edwards translation, having studied MHG and German. It certainly makes a valid edition of a difficult original, rather more like Jean-Paul!

I am currently working on a complete English translation of Parzival in rhyming couplets, having translated all of Chretien de Troyes Romances, The Romance of the Rose, and Gottfried’s Tristan, in rhyming couplets, previously, oh and Marie de France. Proof of madness or proof of the pudding as regards Parzival? You’ll have to wait and see! The previous works mentioned are available if you want to sample them. Parzival should be available online summer 2020. All works on my Poetry In Translation site are free for non-commercial use. For those who think free means low quality, try the site and prepare to be surprised.

Dear Tony, That sounds great! I wish you luck, even if you are a bit mad. I’m so sorry this comment only just got approved! I didn’t get an email notification about it…probably went in my spam 🙁