Well, that was fast. After expressing a wish that A. S. Kline would live to complete his new verse translation of Wolfram’s Parzival, (as Chrétien de Troyes failed to do with his own Perceval), I got an email from him with a link to the finished product on April 14th.

And I’m enjoying it very much. I haven’t been trawling it for minor errors, but I can report that it conveys Wolfram’s tale of Parzival in well-written rhyming couplets. If that sounds good to you, read it here.

My other post on Parzival only covers prose translations. Those are in a different world from verse translations. They’re more academic, produced for scholars who want to know precisely what Wolfram said and—insofar as this is possible for a translator to convey—how he said it. Certainly you can read them for fun, but…not a lot of people do.

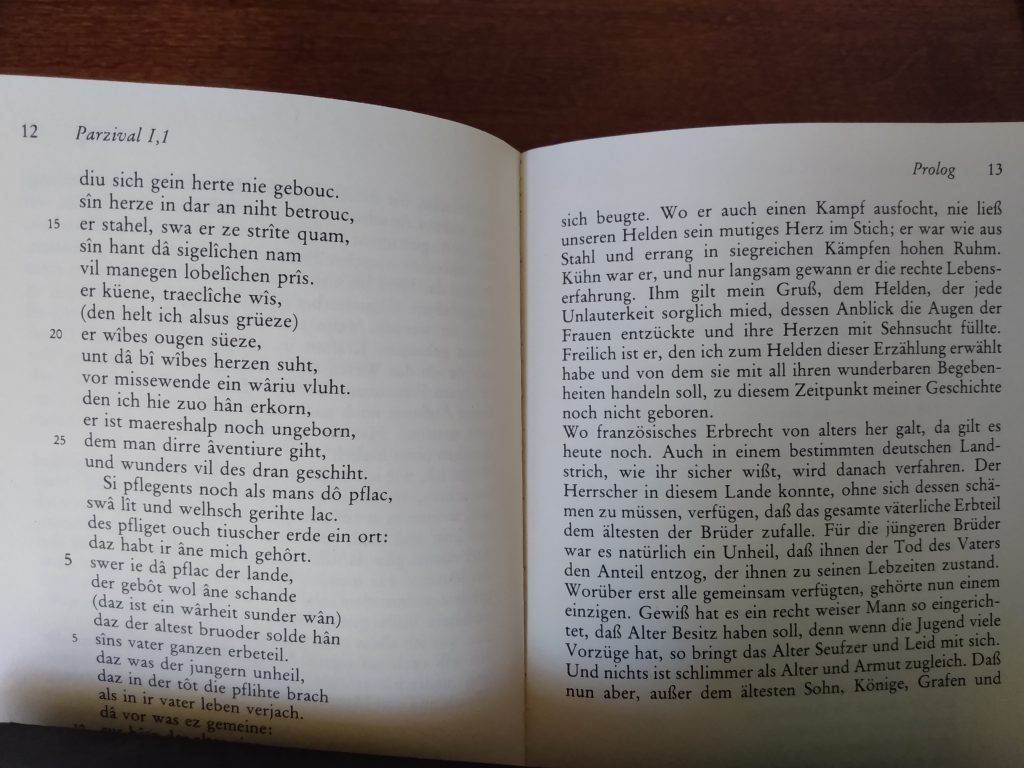

In a sense, verse translations are less accurate than prose translations because of all the juggling and refashioning that must be done to make them rhyme and scan. However, in another sense they are more accurate because, as poems, they give you an experience that is closer to that of the original audience. The prose translations are interesting and informative, but because they’ve changed both the language and the literary genre, the poetic experience is quite disrupted. Compare a prose version of this passage from Parzival to a rhyming one:

This flying image is far too fleet for fools. They can’t think it through, for it knows how to dart from side to side before them, just like a startled hare. Tin coated with glass on the other side, and the blind man’s dream—these yield a countenance’s shimmer, but that dull light’s sheen cannot keep company with constancy. It makes for brief joy, in all truth. [Cyril Edwards]

Or

Now, such a winged metaphor,

Flies all too fast for the unsure,

Slower minds will grasp it not.

It will speed past, and be forgot,

Gone flying like a startled hare.

Thus with a dark mirror we fare,

Or a blind’s man’s dream, all dim

Do features seem, to us and him;

They shine not with a steady light,

Grant but a momentary delight. [A. S. Kline]

Feel the difference? Edwards gets points for precision, Kline for sensibility.

You might wonder whether a poem can ever really be translated. According to the venerable linguist Roman Jakobson, “The pun, or to use a more erudite, and perhaps more precise term—paronomasia, reigns over poetic art, and whether its rule is absolute or limited, poetry by definition is untranslatable. Only creative transposition is possible: either intralingual transposition—from one poetic shape into another, or interlingual transposition—from one language into another, or finally intersemiotic transposition—from one system of signs into another, e.g., from verbal art into music, dance, cinema, or painting.” That may be so, but a good interlingual transposition is worth something, right?

Market forces have decreed that Jessie Weston’s transposition from 1894 is worth $0.99 as a digital download, so I got it to compare with Kline’s. Here are their versions of the two passages presented as samples in my post on prose translations:

| Kline | Weston |

| For I shall now retell a story, That doth speak of great loyalty, Womanly womanhood, anew, And a manly manhood, so true, In every trial, his steel prevailed, His heart within him never failed, While his hand, in battle, likewise Seized on many a glorious prize; Honour-seeking, in nature slow, (For thus do I hail my hero) A sweet sight to woman’s eye, Yet a bane to the heart, thereby; Yet one, indeed, that shunned all wrong. Is yet unborn to this fine tale, Yet shall be born here, without fail, The lad of whom this story’s told, With all its wonders that I unfold. | A tale I anew will tell ye, That speaks of a mighty love; Of the womanhood of true women; How a man did his manhood prove; Of one that endured all hardness, Whose heart never failed in fight, Steel he in the face of conflict: With victorious hand of might Did he win him fair meed of honour; A brave man yet slowly wise Is he whom I hail my hero! The delight he of woman’s eyes. Yet of woman’s heart the sorrow! ‘Gainst all evil his face he set; Yet he whom I thus have chosen my song knoweth not as yet, For not yet is he born of whom this wondrous tale shall tell, And many and great the marvels that unto this knight befell. |

| ‘OPEN!’ To whom? Who goes there? ‘To enter your heart thus, I would dare.’ ‘Then you try too narrow a space.’ ‘How so? Can I not seek a place? I promise not to jostle and press, I would tell you wonders, no less.’ ‘Is’t you, Lady Adventure? Pray How does he fare, your knight, this day? | ‘Ope the portal!’ ‘To whom? Who art thou? ‘In thine heart would I find a place!’ ‘Nay! If such be thy prayer, methinketh, too narrow shall I be the space!’ ‘What of that? If it do but hold me, none too close shall my presence be, Nor shalt thou bewail my coming, such marvels I’ll tell to thee!’ Is it thou, then, O Dame Adventure? Ah! Tell me of Parzival, What doeth he now my hero? |

As you can see, Weston’s style is solidly Victorian, which is fine for people who like that kind of thing. But I’m happy to have a fresh version.

Regarding the bold lines above, it’s always interesting to see how translators handle the key description of Parzival, “er küene, traecliche wis.” Members of the prose gang render it variously as “A brave man slowly wise” (Mustard & Passage), “Dauntless man, though laggard in discretion!” (Hatto), and “Bold was he, laggardly wise” (Edwards), while the modern German prose side of the Reclam edition says “Kühn war er, und nur langsam gewann er die rechte Lebenserfahrung” (“He was bold, and only slowly did he gain the right life experience”).

Kline’s “Honour-seeking, in nature slow” may seem an outlier, but how do knights seek honor in chivalric tales? Through deeds of valor, of course, i.e. by being brave and bold, so I’m cool with that. Wolfram doesn’t say anything about “nature,” but “in nature slow” gives me the same impression as “he’s a slow boy,” which feels right for Parzival, although it does raise the question of whether it was his own nature or his isolated upbringing that made him “slow”—a question that would require its own blog post, essay, or tome.

Edwards’ “laggardly” is a good reflection of Wolfram’s eccentric diction (and the same goes for his “storywise, yet unborn” – see the other bold lines above about being “unborn to this fine tale”); this is an aspect of Wolfram’s style that doesn’t come through very strongly in either Kline or Weston.

In the intro to his prose edition, Edwards specifies aspects of Wolfram’s Parzival he wished to preserve in his translation: richness of imagery, neologisms and nonce words, personification, the “frequent grammatical leaps and bounds” of its syntax, a sense of “playful arrogance,” and unusual constructions such as double or triple genitives (e.g. “woman’s eyes’ sweetness”). Some of these considerations will inevitably fall by the wayside if you set out to translate the work as rhyming couplets—you can’t do everything.

This is why I said in my previous post that “no one in our time has been insane enough publish a rhyming-couplets version. Jessie Weston did it in 1894, but translation standards were looser then.” What I meant was that with our current standards for literary translation, anyone who puts a rhyming version out there and dares to call it a “translation of Wolfram’s Parzival” will be swarmed by nitpickers with endless quibbles about the lack of double genitive constructions or whatever.

In contrast to Edwards’ warning that his translation imitates Wolfram by giving the reader “a rough ride,” Kline says he decided to “tidy Wolfram up” so the text could be “one to enjoy for the general reader.” Weston described her verse translation as both “faithful to the original text and easy to read,” which is kind of hilarious considering that the original text is notoriously hard to read. But by “faithful,” she probably meant “tells the same story.” Pan out a bit and you’ll see this approach is in tune with medieval literature. Someone handed Wolfram an incomplete and rather basic French tale of Perceval and the Grail and asked him for a German translation, and he responded by producing this unbelievably elaborate shroom trip. If he could see how many pains scholarly translators are taking with his work today, I think he’d be perplexed. He’d punch them in the arm and say, “Bro, just make up your own version! And make it rhyme!” Then he’d gallop off after a startled hare.