This episode has always been popular – it’s inspired fan merch and was discussed at length in The Atlantic in 2014 – but it’s getting more attention lately as the social media hive mind wrestles with certain issues.

The episode begins with the Enterprise receiving an invitation to establish relations with an alien race, the Children of Tama, aka Tamarians. However, attempts to communicate with the Tamarians have failed on seven previous occasions. Star Fleet deems them incomprehensible. The “universal translator” device helps little because so much of their speech consists of proper names: “Rai and Jiri at Lungha,” says their captain, Dathon, upon meeting the Enterprise crew. “Rai of Lowani. Lowani under two moons. Jiri of Umbaya. Umbaya of crossed roads. At Lungha. Lungha, her sky gray.” The crew are perplexed.

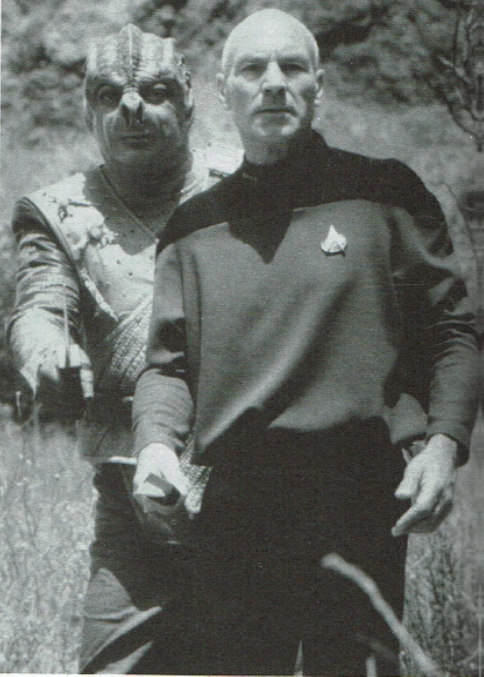

Having failed to communicate their Plan A for establishing relations with The Federation, the Tamarians switch to Plan B, which they call “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra.” They beam Dathon and Picard down to the nearest planet, where the two captains end up fighting a monster with daggers. Meanwhile, Data and Deanna Troi google some proper names mentioned by the Tamarians and realize they are references to mytho-historical people and places. It turns out the Children of Tama communicate entirely through “narrative imagery,” so you have to learn their stories in order to talk to them.

Picard realizes the same thing while fighting alongside Dathon: the heroes Darmok and Jalad learned to understand each other by facing a common enemy at Tanagra, and that is what they are supposed to do now. Dathon is mortally wounded by the monster but spends some quality time by a campfire listening to Picard tell the story of Gilgamesh and Enkidu, before dying secure in the knowledge that he has made a communicative breakthrough. By the time Picard is beamed back up to the Enterprise, he’s learned enough narrative reference points to tell the Tamarian crew what happened down on the planet. Although saddened by the loss of their captain, the Tamarians are overjoyed that someone finally understands them. The episode ends with Picard reading Homer and reflecting that “More familiarity with our own mythology might help us relate to theirs.”

If you watch the episode more than once, you can come up with rough translations for the Tamarian dialogue. For example, after the humans fail to understand “Rai and Jiri at Lungha” (which was presumably a suggestion for a more conventional diplomatic meeting), the Tamarians argue amongst themselves:

DATHON: Darmok. (“We’ll have to fight a monster together.”)

FIRST OFFICER: Darmok? Rai and Jiri at Lungha. (“Fight a monster? No, do what Rai and Jiri did at Lungha.”)

DATHON: Shaka. When the walls fell… (“That’s not working…”)

FIRST OFFICER: Zima at Anzo. Zima and Bakor. (Alternate suggestions based on other stories.)

DATHON: Darmok at Tanagra.

FIRST OFFICER: Shaka! (“It won’t work!”) Mirab, his sails unfurled. (“Let’s go.”)

DATHON: Darmok.

Although I’m old enough to remember the Saturday Night Live skit where William Shatner yells at Trekkies to get a life, I’m still going to ask some serious questions about this language:

Is the language made up of separate words? What we hear is filtered through Star Trek’s “universal translator,” a convenient piece of de facto magic that suffers from none of the characteristic weaknesses of machine translation. (Contrast this with Eifelheim, where the machine translator is conspicuous and quirky.) So we can’t be sure about the structure of the language, but the characters do seem to be saying a series of words. And in addition to proper names, they have many other words in various parts of speech. This should allow them to mix the words up to form new sentences. But instead they’re stuck repeating set phrases. I don’t think there could be a language like this in real life. A culture that values myth, yes, but something this rigid, no.

How do they say anything specific? This seems to be the most common objection — how did these people build a spaceship if they can’t give instructions like “The confinement resolution should be .527” or “Press that button if there’s a power surge in the plasma reactor”? The best answer is probably Ian Bogost’s assertion in his Atlantic article that each mythological reference communicates “a strategy” or “a logic,” which is carried out with no need for “explicit, low-level discourse.” Given how much ants and bees accomplish without explicit, low-level discourse, I’m prepared to believe there could be an alien species operating along similar lines. In fact, The Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion notes that this episode was originally conceived as “a complex and confusing ‘ant farm’ visit,” so insect societies may indeed have served as a model for the Tamarians.

How do they learn their own stories? If they can’t mix and match words to form new sentences, how does anyone tell a story to a child who’s never heard it before? Maybe they attend mystery plays where the stories are acted out with minimal speaking.

When Dathon asks Picard to tell him a story by the campfire, why does Picard say, “But you wouldn’t understand?” They have the translator. It’s a story, and the Tamarians are all about stories. This seems connected to my points 1 and 3 – can they not understand novel combinations of words? Do they not learn their own stories by hearing them told, as we do? We don’t know. Anyway, Dathon does appreciate the tale of Gilgamesh, although it’s not clear what his comprehension level is.

The best answer to these questions is probably “shut up,” because the episode has a value that transcends quibbles.

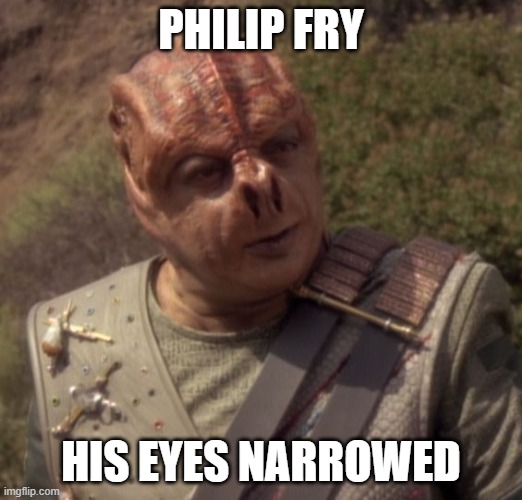

To understand its recent resurgence, let’s consider how discourse has changed over the past decade. Some of the people who used to produce meticulous, link-filled arguments in response to other people who were Wrong on the Internet have moved on to quietism. Others have adopted a posture of being “so tired of having to explain these things.” The most savvy have gone Tamarian and committed to meme culture. Our awareness of the role memes now play in our communication called forth the image of Dathon describing well-known memes in his characteristic style:

I particularly like the last one because it refers to a real-world event that achieved mytho-historic status almost instantly.

And it’s not just Internet memes per se that summoned Dathon to Twitter and Tumblr in 2020. It’s also a sense that as our fractured media environment renders reasoned argument ineffectual, at least between different memetic tribes, archetypal stories begin to shine more brightly.

Americans can’t currently agree on any of what constitutes “the news.” But we can agree that you shouldn’t fly too close to the sun. We can agree that certain things will turn you to stone if you look straight at them. And that sometimes there’s a thing you need to leave behind, and you mustn’t look back at that thing, not even once. Closer to home, perhaps we can agree it’s right to walk six miles to return three cents to a customer you overcharged, or fess up to chopping down your Dad’s cherry tree.

The Tamarians communicate through “narrative imagery,” and so do we all, now. The distracted boyfriend meme isn’t a myth per se, but it’s a kind of microstory that everyone understands. Like the Children of Tama, we know how to express our thoughts according to its logic. And as they circulate, memes acquire layers and shades of meaning that add to their communicative power. Unfortunately, they also have the power to spread propaganda and stoke groupthink and enmity. Use them wisely.

Leave a Reply to lefreeburn Cancel reply