I have a reader who maintains that Disney’s Bambi practically ruined what good disposition he had, if he had any. He’s also been haunted by the cold war since listening to the Army-McCarthy hearings in his crib, and one of the cold-war specters haunting him is Whittaker Chambers, who first translated Felix Salten’s Bambi into English. After reading a New Yorker article that triggered his bad cervine/political memories, he kindly bought me the original German Bambi, Chambers’ translation, and a new translation that just came out, and asked me to write about them. So here’s an introductory post about the book, and the next one will get into the details of the translations.

Felix Salten was a Viennese writer of the Café Griensteidl’s “Young Vienna” school. He produced a wide variety of journalistic pieces, art and theater reviews, plays, short stories, essays and novels. Bambi was one of many stories he wrote about animals, whom he observed closely and regarded with deep affection and solemn awe. As a careful hunter (in contrast to careless Yosemite Sams like Archduke Franz Ferdinand), he appreciated the terrible grandeur of the circle of life.

People who’ve seen the film are often surprised by how much pain, sorrow and death are in the book, although of course Disney’s version also has its dark moments. Recent articles have described it as “sugary” or “a syrupy love fest” and that’s partly true, but the sight of Bambi helplessly calling for his slain mother as the forest fades to black, white and blue is what robbed my reader of his good disposition (if he had any). I also asked my mom about it – she was born in 1938 and saw it at age 4 – and she said this:

It was the first movie I was ever taken to. We went to Grandma Berry’s in Neponset and the good movie theater was in Kewanee. I think I may have been with other cousins, don’t remember, as there were 3 of us girls. I was so stunned by the death of Bambi’s mother that I couldn’t figure out why they took me to see it. It created a fear that I could lose my mother, which I never had considered at that age.

By the time I saw it at the same age in 1982, I was too jaded by TV to be seriously upset by it. But I did remember the two distressing parts. My young mind conflated them so that I recalled Bambi’s mother as having been shot while trying to flee the forest fire. I can still replay the relevant scene in my head (a scene that doesn’t actually exist because the fire and the shooting are separate incidents). The movie also shows us the hardship of forest life in winter, a violent clash between bucks during mating season, and a fight with hunting dogs, so the book’s harsh elements weren’t eliminated. However, it’s certainly true that the movie is much cuter and less profound than the book.

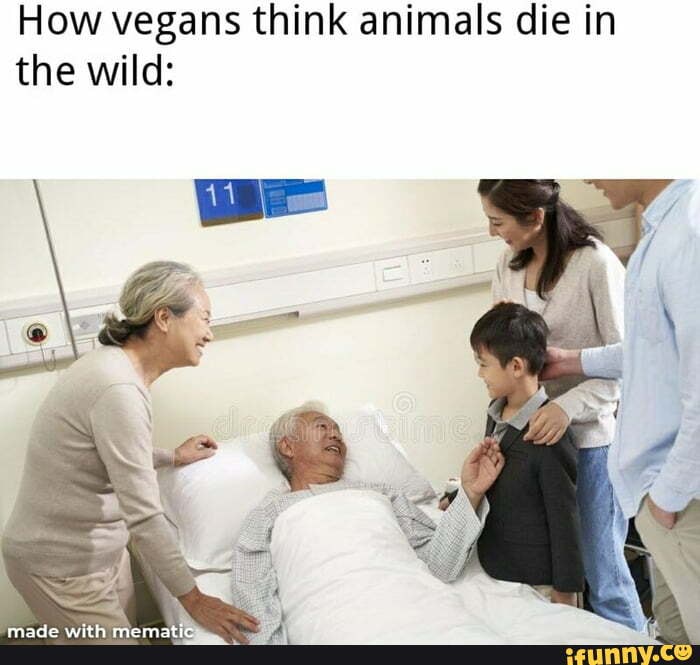

Whereas the forest in Disney’s Bambi is a carefree playground when Man’s away, Salten’s Bambi opens with his mother’s harsh and solitary labor and quickly moves on to young Bambi witnessing a mouse’s death by ferret and absorbing his mother’s fear of danger. The danger she fears is Man (and let me just note here that as an American and a Midwesterner, I think this book would have been quite different had the author lived in a country with wolves and coyotes). Other, smaller animals also live in fear of forest predators. The book disabuses readers of the same naive ideas about nature that inspired this meme:

But Salten’s work is first and foremost a meditation on the joys and sorrows of all living things, their beauty, prowess and dignity, their vulnerability – which Man, despite his devious arts, ultimately shares – and the transcendent sublimity of nature, created and watched over by a mysterious supreme being. Salten focused on “simple and eternal things” as Beverley Driver Eddy writes in her excellent biography, Felix Salten, Man of Many Faces. Many threads are woven into Bambi: Salten’s own love for nature and animals, the Bildungsroman genre, Aesop’s fable of the dog and the wolf, real-life anecdotes, a vision of prelapsarian harmony between man and beast, a yearning for justice, and a delight in imagining animal equivalents of human manners and morals. Like any mature work of art, it can be appreciated by all kinds of people with different perspectives, who may draw insights from it that are so deep they are hard to articulate.

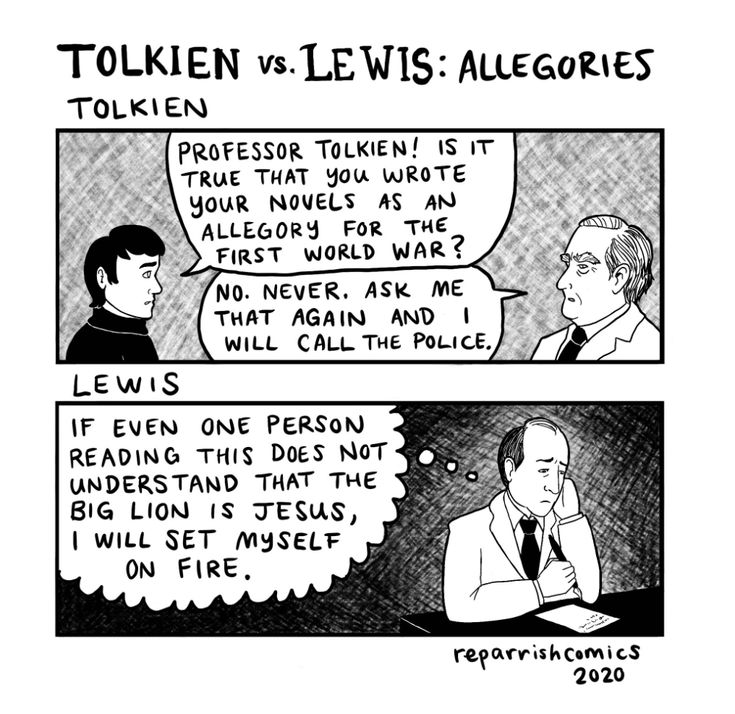

With that in mind, I’ll have to address the fashionable notion that Bambi is a simple allegory about persecution of the Jews in Europe or of ethnic minorities in general. The New Yorker article states: “[…] authors do not necessarily get the last word on the meaning of their works, and plenty of other people believe that Bambi is no more about animals than Animal Farm is. Instead, they see in it what the Nazis did: a reflection of the anti-Semitism that was on the rise all across Europe when Salten wrote it.”

Salten himself was a Jew living through the cycle described by Theodor Herzl, “We are naturally drawn into those places where we are not persecuted, and our appearance there gives rise to persecution.” Like the rest of Vienna’s Jewish literati, he had a complex identity and a sharp awareness of man’s inhumanity to man. This aspect of his personal perspective would certainly have influenced his work to some extent. For example, the deer community’s discussion in Chapter 9, where eschatological hopes of the lion lying down with the lamb alternate with an old doe’s wry one-liners, has a Jewish vibe.

But to interpret the book as an allegory of human affairs along the lines of Animal Farm is a disservice to the author. I hope I managed to emphasize sufficiently above that Salten was fascinated by and devoted to animals per se in a way Orwell, or indeed Aesop, was not. (The first “farm book” that springs to mind when I think of Bambi is not Animal Farm but Charlotte’s Web.) And as a writer with good artistic sense, he aimed much higher than connect-the-dots social allegory.

Note that the New Yorker quote above claims that the Nazis saw Bambi as an allegory. That article goes on to say “Does all this make Bambi a parable about Jewish persecution? The fact that the Nazis thought so is hardly dispositive – fascist regimes are not known for their sophisticated literary criticism […]” I searched the internet for evidence of that claim, and found no Nazi denunciations of Bambi quoted anywhere. Then I combed through Eddy’s biography of Salten, which discusses the banning of his books by the regime in the mid-thirties, and found no evidence there either. So then I wrote Eddy an email to ask if any Nazis had ever made statements about Bambi being a parable about Jewish persecution, and she said she never found any evidence for that in her research. She added that if they had viewed it that way they probably would have burned it in 1933 – instead, it was banned in 1935 and never burned – and that if she remembered correctly, it was the last of Salten’s books to be removed from libraries and bookstores. I’m not sure where the author of the New Yorker piece got this idea, but I’m pretty sure it’s mistaken.

That said, I thought the New Yorker article was very good on the whole. My specter-haunted reader thought so, too. It’s interesting to see the original Bambi getting renewed attention. See my next post for more attention from me, about the nitty-gritty of the German-to-English translations.

I’ve never seen or read any version of “Bambi,” but it’s interesting to read about the Viennese milieu it came out of. Maybe there should be a sequel, where Bambi has to deal with 12-tone music and psychoanalysis.

Laura, I appreciate the breadth and the depth of your analysis. I think you must have a very insightful relative, let’s say, an uncle.

Thanks for the interesting read – I never thought of Bambi as anything else than – or more than – a “syrupy film”. Seems I was wrong. I live in a forest with deer all around, so this theme resonates.

This year marks the one hundred year anniversary of the first (serialized) publication of Bambi in Germany, as well as the seventy year anniversary of the publication of Witness. It is also the eighty year anniversary of the American premier of that great destroyer of countless children’s happiness and sense of well-being, the Walt Disney Bambi movie.

So, perhaps there was some sort of numerological imperative (and not just her unhappy reader) that caused Laura to embark upon the intellectual and scholarly project that resulted in this excellent, highly informative and well-structured essay. It will, I believe, eventually be regarded as a valuable addition to the literature concerning “verlängertes-emotionales-Trauma-für-das-innere-Kind-das-aus-der-Bambi-Film-Exposition-resultiert” (prolonged emotional trauma to the inner child resulting from Bambi film exposure).

Speaking of traumas, Whittaker Chambers has been accused of inflicting not just the Bambi story on the American public, but hastening the emergence on the national political scene of Richard Nixon (as a result of the Hiss case), as well as a perversion of conservatism that has caused a great variety of morbid symptoms to appear and metastasize in the body politic, at least according to George Will:

‘Witness became a canonical text of conservatism. Unfortunately, it injected conservatism with a sour, whiney,

complaining, crybaby populism… Chambers wallowed in cloying sentimentality and curdled resentment about

“the plain men and women” – “my people, humble people, strong in common sense, in common goodness” –

enduring the “musk of snobbism” emanating from the “socially formidable circles” of the “nicest people”

produced by “certain collegiate eyries.” ‘

But you can’t say that Whittaker Chambers didn’t have an interesting life. I had forgotten a lot of the details, but they are all in his Wikipedia entry (in which Bambi gets only the briefest of mentions). He even wound up as a Quaker…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whittaker_Chambers

I saw the news today (oh boy). The Governor of Florida and the state legislature, to great acclaim from some quarters, have moved to punish the Disney company for not supporting their efforts to “protect” young children. Sorry, people – you are many decades, and at least one animated feature, too late…