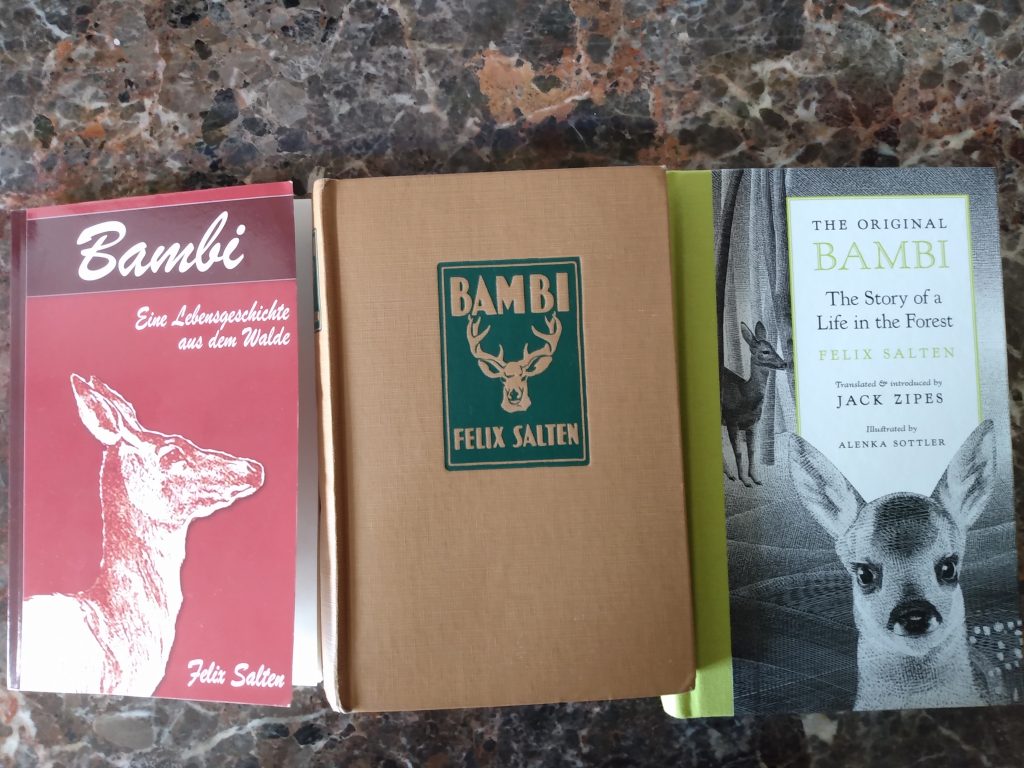

See below for the introductory post about Bambi. This post compares the old translation and the new translation; let’s call them OT and NT.

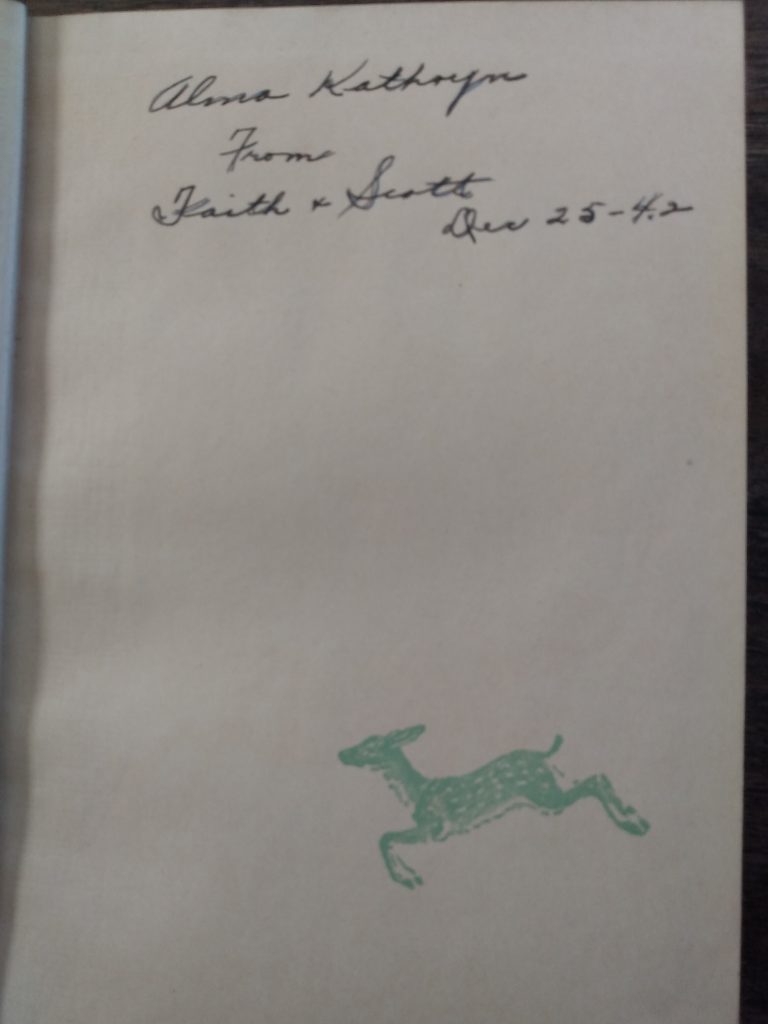

My edition of the OT was kindly purchased for me by my traumatized reader (see intro post) from a used book shop in Tennessee. It had previously been given as a Christmas gift to one Alma Kathryn in 1942, the year the Disney movie came out. Although recent articles have emphasized the extent to which the film eclipsed the book, it seems at least some people were inspired to buy the book after seeing the film.

According to the New Yorker article, it has been claimed that the OT “mistranslated Salten, flattening both the political and the metaphysical dimensions of the work.” However, the author of that article goes on to say, “that claim is borne out neither by examples in the introduction [to the NT] nor by a comparison of the two English versions, which differ mainly on aesthetic grounds.”

One sentence might suffice to give you a sense of their aesthetic differences (part of a description of Bambi as a disoriented newborn):

German original: Es nahm auch noch keinen einzigen von all den Gerüchen wahr, die der Wald atmete.

OT: Nor did he heed any of the odors which blew through the woods.

NT: Nor did he perceive a single one of the smells that the forest exuded.

Moving on, is there any evidence that the OT contains significant errors, and do they “flatten the political and metaphysical dimensions of the work”?

The OT is often accused of sloppy taxonomy, e.g. “Eisvogel” (“kingfisher”) is translated as “hummingbird.” Was that an error or just an adaptation for American readers who wouldn’t be familiar with kingfishers? To add to the confusion, the NT translates “Eisvogel” as “warbler.” Why? It’s not an option in any of my reference books, so it seems like another error or adaptation. This is a recurring problem—titmouse or chickadee? Ferret or polecat?—but frankly not very interesting to most readers.

The error that most jumped out at me from the OT was as follows: the kingfisher from the paragraph above is quite anti-social. Another bird (sedge-hen or coot?) tells Bambi that the kingfisher has never said a word to anyone. Bambi replies, “Poor thing…” with the ellipsis indicating a pensive, sorrowful tone (rather than an incomplete sentence). (In German: “Der Arme…” with “Arme” capitalized because it is an adjectival noun.) Presumably thrown off his game by the ellipsis and a failure to notice the capital A, Chambers (author of the OT), has:

“The poor…” said Bambi.

Then I checked the NT and was surprised to see the exact same error, only ramped up:

“The poor…” Bambi began to say.

(The new translator has added the idea that he “began” to say it.)

Seeing this in both books made me doubt my judgement so I consulted two native speakers with excellent writing skills and they both confirmed it could only be “poor thing” and the ellipsis was there to signal his tone.

So, as we can see, both books contain errors (as do most long translations, including mine). But do the errors in the OT really give readers a highly distorted experience of Bambi, as some have claimed?

Some examples to back up that claim can be found in an article by Sabine Strümper-Krobb in the journal Austrian Studies. Strümper-Krobb closely compared the German original to Chambers’ translation and found that Chambers often translated anthropomorphic language into language that is more conventionally about animals. See this table for examples:

| Salten | Chambers | Should be |

| Das waren die Tage, in denen Bambi seine erste Kindheit verlebte. | These were the earliest days of Bambi’s life. | childhood |

| Überall gab es solche Straßen, sie liefen kreuz und quer durch den ganzen Wald. | There were tracks like this everywhere, running criss-cross through the whole woods. | streets (referring to deer trails) |

| Er kam mitten im Dickicht zur Welt, in einer jener kleinen, verborgenen Stuben des Waldes… | He came into the world in the middle of the thicket, in one of those little, hidden forest glades… | rooms |

| Hier in dieser Kammer war Bambi zur Welt gekommen. | Bambi had come into the world in this glade. | chamber |

| Dann küsste sie wieder ihr Kind…. | Then she kissed her fawn again… | child |

| “Das sind die Kleinen.” | “Those are ants.” | the little ones |

| “Weil wir niemanden töten.” | “Because we never kill anything.” | anyone/anybody (this is Bambi’s mother saying deer don’t kill other animals) |

| Ganz langsam schritten sie durch einen Saal himmelhoher Buchen. | They walked very slowly through a grove of lofty beeches. | hall |

| der Alte, der alte Fürst | the old stag | The old one, the old prince |

| Liebeszeit der Könige | mating season | the kings’ time of love |

| Krone | antlers | crown |

| die anderen gekrönten | the other bucks | the other crowned ones |

In other words, unconventional words and phrases that make the animal world seem more human are translated as conventional terms relating to animals and the forest.

I think (though it’s pure speculation) that the reason for this is as follows: One thing translators do all the time is adjust phrases to make them sound more “normal” in the target language. You read the source text and understand it but you also think, “That’s not how we say that,” and you adjust it to bring it into line with customary English usage. So, for example, you have a German phrase that translates to “Issuing threats against the world community” and you change it to something like “Threatening the global community.” I suspect Chambers was going through this book thinking “we don’t call antlers ‘crowns’ in English” and “no one would call a forest glade a ‘room’” and just making it all sound more normal. What he didn’t realize was that Salten’s word choices weren’t normal in German either and of course, unusual diction in the source should be translated as something equally unusual in the target. Chambers had learned German fairly recently and therefore hadn’t read widely enough to make judgements about which word choices are unusual in that language. That’s what I suppose, anyway.

How much did Chambers’ less-anthropomorphic diction affect English readers’ experience of the story? I’d say a little bit but not that much. When we read of Bambi and his mother walking on “streets” in the forest, we’re likely to picture streets in a town and consider that deer feel the same way about their trails as we feel about our streets. Chambers’ “tracks” and “trails” don’t call forth the same thoughts. However, the book as translated by Chambers is still deeply anthropomorphic. It couldn’t be otherwise, with passages like this, where Bambi considers striking up a conversation with the intimidating old stag:

Bambi did not know what to do. He had come with the firm intention of speaking to the stag. He wanted to say, “Good day, I am Bambi. May I ask to know your honorable name also?”

Yes, it had all seemed very easy, but now it appeared that the affair was not so simple. What good were the best of intentions now? Bambi did not want to seem ill-bred as he would be if he went off without saying a word. But he did not want to seem forward either, and he would be if he began the conversation.

The stag was wonderfully majestic. It delighted Bambi and made him feel humble. He tried in vain to arouse his courage and kept asking himself, “Why do I let him frighten me? Am I not just as good as he is?” But it was no use. Bambi continued to be frightened and felt in his heart of hearts that he really was not as good as the old stag. Far from it. He felt wretched and had to use all his strength to keep himself steady.

The old stag looked at him and thought, “He’s handsome, he’s really charming, so delicate, so poised, so elegant in his whole bearing. I must not stare at him, though. It really isn’t the thing to do. Besides, it might embarrass him.” So he stared over Bambi’s head into the empty air again.

“What a haughty look,” thought Bambi. “It’s unbearable, the opinion such people have of themselves.”

Did you read that and think, “I don’t get these deer, they don’t seem very human to me”? They might as well be eyeing each other up during intermission at the Vienna Court Opera.

Interestingly, Chambers uses “people” in that last line, whereas the German says “Es ist unerträglich, was so einer sich einbildet” – “so einer” meaning “such a one.” So in this case Chambers has added an explicitly human word where there wasn’t one in the German original! Which makes me fairly certain he didn’t have a policy of de-anthropomorphizing Salten’s forest dwellers and his word choices in the table above are just examples of overly cautious handling of unusual phrases.

In summary, there’s room for improvement in the OT but on the whole, it’s well-written, true to the spirit of the book, and accurate enough that little Alma Kathryn didn’t have a radically different reading experience from her counterparts in the German-speaking world.

As for the NT, it corrects some but not all of the discrepancies noted in the table above. Where Salten has “Straße” for a deer trail, this version has “path,” which is unsatisfactory in the same way as the old translation. But it does correctly say “We never kill anybody” (instead of “anything”) and “chamber” for “Kammer.” The writing style is quite different from the OT and readers can decide for themselves which one they prefer. The OT has the advantage of having been written in the same decade as Salten’s book, so its style has a natural compatibility with the original that is hard to achieve almost 100 years later. I would recommend the OT to most readers based on the quality of its prose.

I could go on and on about little details in these books, but I suspect most of my readers will be satisfied with the few examples cited so far. Don’t hesitate to leave a comment if you would like to know more.

I really enjoyed reading these two posts. I never saw the movie but I read the book (the OT) as a child. Your posts brought back some memories of how I felt when reading the book, although I don’t remember many specifics of the story. It didn’t ruin my disposition, but I have a bit of a sad or uneasy feeling about the experience.