This 1955 book by Milton Mayer, reissued in 2017 by University of Chicago Press with a helpful afterword by Richard Evans, is worth your time if you are interested in human beings.

Mayer, a Chicago native, worked as a freelance journalist and taught Great Books seminars with Mortimer Adler and Robert Hutchins (he gets a few mentions in Alex Beam’s excellent survey A Great Idea at the Time: The Rise, Fall, and Curious Afterlife of the Great Books). Descended from German Jews who had fled to America after the failed revolutions of 1848, he also belonged to the Society of Friends and coined the phrase “Speak truth to power.”

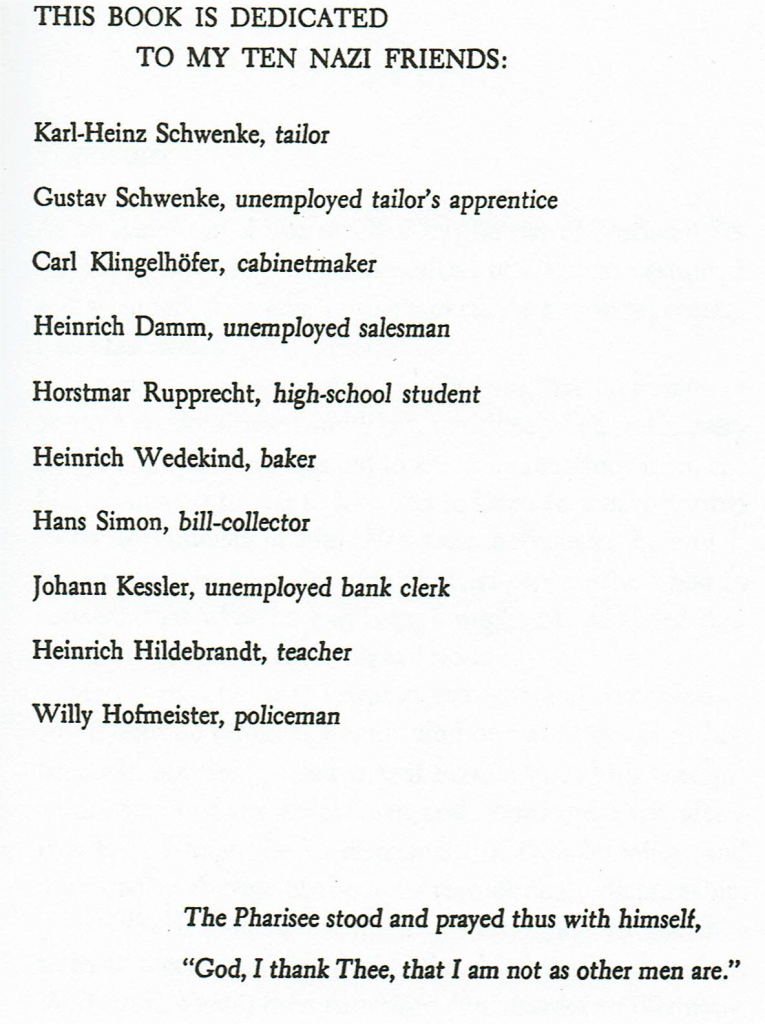

They Thought They Were Free is based on a project he undertook in Germany with the support of the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt (Theodor Adorno et al). He settled in Marburg (called “Kronenberg” in the book) and conducted a series of lengthy interviews with ten former Nazis in the area, hoping to get a detailed sense of how “a typical German of small status” developed into a National Socialist.

He told them he was a Professor from America who wanted to learn about what life had been like in Germany during the war. His approach was friendly and humble — he arrived at their homes on foot, bringing gifts, and listened sympathetically to whatever they had to say. Sometimes their children played with his. He never told them he was Jewish or that he had access to their denazification records, which would have been a bit of a conversation killer. Surprisingly, he didn’t speak much German and believed this to be an advantage: if his subjects could feel they were talking down to him, teaching him to say “auf Wiedersehen” and whatnot, they would feel less intimidated and be more likely to speak freely (he did bring along an interpreter).

The resulting book has compelling personal stories and valuable insights. It is definitely worth reading. However, it also gets bogged down in musings on national character that will seem tiresome and cliché to most readers nowadays. I actually lost patience with the second half and didn’t finish it.

At its best, though, the book offers the kind of individual moral histories that everyone can learn from:

But the one great shocking occasion, when tens or hundreds or thousands will join with you, never comes. That’s the difficulty. If the last and worst act of the whole regime had come immediately after the first and smallest, thousands, yes, millions would have been sufficiently shocked. […] But of course this isn’t the way it happens. In between come all the hundreds of little steps, some of them imperceptible, each of them preparing you not to be shocked by the next. Step C is not so much worse than Step B, and, if you did not make a stand at Step B, why should you at Step C? And so on to Step D.

And one day, too late, your principles, if you were ever sensible of them, all rush in upon you. The burden of self-deception has grown too heavy, and some minor incident, in my case my little boy, hardly more than a baby, saying “Jew swine,” collapses it all at once, and you see that everything, everything, has changed and changed completely under your nose. The world you live in – your nation, your people – is not the world you were born in at all. The forms are all there, all untouched, all reassuring, the houses, the shops, the jobs, the mealtimes, the visits, the concerts, the cinema, the holidays. But the spirit, which you never noticed because you made the lifelong mistake of identifying it with the forms, is changed. Now you live in a world of hate and fear, and the people who hate and fear do not even know it themselves; when everyone is transformed, no one is transformed. Now you live in a system which rules without responsibility even to God. The system itself could not have intended this in the beginning, but in order to sustain itself it was compelled to go all the way.

You have gone almost all the way yourself. Life is a continuing process, a flow, not a succession of acts and events at all. It has flowed to a new level, carrying you with it, without any effort on your part. […] Suddenly it all comes down, all at once. You see what you are, what you have done, or, more accurately, what you haven’t done (for that was all that was required of most of us: that we do nothing). You remember those early meetings of your department and the university when, if one had stood, others would have stood, perhaps, but no one stood. A small matter, a matter of hiring this man or that, and you hired this one rather than that. You remember everything now, and your heart breaks. Too late. You are compromised beyond repair.